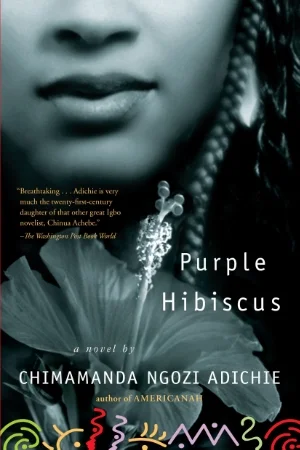

BOOKISH: Purple Hibiscus

“Things began to fall apart at home when my brother, Jaja, did not go to communion and Papa flung his heavy missal across the room and broke the figurines on the étagère.”

From the opening sentence, it is clear that something is amiss.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie never fails to jostle my emotions and disrupt my spirit when I choose to delve deeper into the jungle of her stories. Purple Hibiscus is no exception. I cannot believe it has taken me so long to participate in this experience. Yes, it is indeed a psychological experience. With too many climaxes to name, it is difficult to describe the autocracy and domination so vividly described in this brilliant novel.

Purple Hibiscus is, in many ways, a typical coming-of-age story, about the sexual and moral awakening of a shy, bookish teenager transformed through tragedy into a young adult who is more outspoken. At the beginning of the novel, Kambili and her older brother Jaja are insecure, timid, almost machine-like in their interactions with family, friends and schoolmates. As we jump on this emotional rollercoaster, we watch as they become courageous and more self-assured. But there is a dark current that encircles the story. To the outside world, they and their reserved, modest mother Beatrice, are living the dream life in Enugu (in Nigeria). However, behind the privileged walls of their manor, life is less than peachy. Around the bare bones of the plot, Adichie reveals detail upon detail of the Achike's domestic life -- a life of lists and schedules, fervent religion and violence at the hands of Eugene "Papa" Achike.

Papa's religious fanaticism and autocratic bearings on his family incapacitate and imprison those he loves - yet ironically punishes - the most. He is a person so completely affixed to the Western way of thought and behavior, that he stops at nothing to see it enforced in his household. A man of extremes, he is absorbed by raw bouts of emotion -- extreme love and, worse, extreme anger. He doles out severe punishments for minor infractions, leaving physical and emotional scars in his wake. His family lives every minute in fear of the consequences when perfection is not attained, constantly seeking his approval. Adichie’s subtle descriptions of Papa’s stifling presence and actions of sheer terror are extremely well done -- my heart wrestled between trying to figure out what may have led to his behavior and an ever-present dull ache for the pain wrought on his family.

The chill begins to thaw, and something new begins to replace the anger and pain. A sunbeam reflects upon this grim picture in the face of Papa's widowed sister Aunt Ifeoma, who invites the children to spend time with her family in Nsukka. Visiting their aunt and her three children, Kambili and Jaja get a chance to see how a more ordinary, relaxed family functions. Yet even there, while the two are free from their father’s physical presence, they can never quite shake off their father’s influence. Nevertheless, the visit to Aunty Ifeoma's modest home in the university apartments begins a series of life-altering experiences with far-reaching effects for everyone in the Achike family.

“These are the people who think that we cannot rule ourselves because the few times that we tried, we failed, as if all the others who rule themselves today got it right the first time. It is like telling a crawling baby who tries to walk, and then falls on his buttocks, to stay there...As if the adults walking past him did not all crawl, once.”

While the themes of domestic violence and religious piety transcend throughout the novel, Adichie courageously raises other poignant matters: the validity of Igbo traditional religion; discussing chastity when a young priest becomes the object of a school girl crush.

However, the undercurrent of the novel is the political environment of Nigeria. All around them, Nigeria is slowly falling apart just as the family does. A close family friend is assassinated and a violent coup causes Aunt Ifeoma to leave the country for the United States of America. Bright intellectuals and educators flee the country to escape intimidation, rising dictatorial rule and deteriorating social services, and to maintain intellectual freedom and autonomy. Adichie eloquently captures the resilience of the citizens amidst the prevalence of mounting poverty, threats of assault and political instability.

“Silence hangs over us but it is a different kind of silence. One that lets me breathe. I have nightmares about the other kind, the silence of when Papa was alive. In my nightmares, it mixes with shame and grief and so many other things that I cannot name, and forms blue tongues of fire that rest above my head, like Pentecost, until I wake up screaming and sweating.”

This story is about silence, of things left unsaid. Throughout the book, characters struggle with the task of communication. Not enough and too much. Throughout the novel, Kambili watches others in an effort to understand and the narration is her chance to speak up and find her voice.

There is a shroud of silence in Adichie's portrayal of violence. The physical violence he administers is hinted at but never demonstrated in detail. Many times Papa abuses his family behind closed doors, shielding the reader from overt incursions that take place. Adichie creates the haunting atmosphere of abuse in the same nature in which abuse thrives: in the shadows, indirect and dishonest. Papa’s outbursts hang in the air and build a tension so thick, it clouds the mind. The reader tries to seek understanding about how it continues for so long. But, it is only when abused people begin to see their own self-worth, by either receiving validation or seeking help, that abuse is brought to light. By the end of the book, despite the tragic circumstances, there's a hesitant comfort that the light at the end of the tunnel looms closer.

This novel is not completely depressing, though. Kambili's cousin, Amaka, is an avid fan of Fela Kuti and is a confident and fierce feminist. There is freedom of expression in Aunty Ifeoma's household, and she, grandfather and her children laugh without reservation. There are moments of affection, warmth and love, so gloriously earned in relief from all the suffering.

Purple Hibiscus is truly a compelling novel; an ardent, cerebral journey. As the final chapter comes to a close, there is renewed hope and the reader is left wishing that the family heals and is able to put the turmoil behind. Freedom is imminent for all of them, so close that perhaps we can finally let out our breaths and relish in the bloom of a purple hibiscus.